Labor Day Reflections 2022: The Divine Urgency of Labor Solidarity

Last year we initiated a special edition of Interventions for Labor Day, featuring a series of reflections that connected the assigned scripture readings in the Christian tradition (based on the Revised Common Lectionary) with contemporary matters of labor justice. This year we seek to continue and expand the conversation, engaging the Christian tradition about the diverse faith-rooted origins of the call to economic justice.

The written reflections and video conservations that follow — featuring Wendland-Cook leadership, student fellows, and faith and community colleagues that are engaged in various aspects of economic justice ministry, labor and community organizing, and justice-seeking theological work — are offered with lay and ordained faith leaders and allied community partners in mind. We hope to share ideas, stories, and insights on how to preach, teach, and organize around the issues of labor and economic justice during and following the Labor Day holiday, and how these matters are inseparable other forms of oppression (racism, sexism, homophobia, the ecological crisis, etc.).

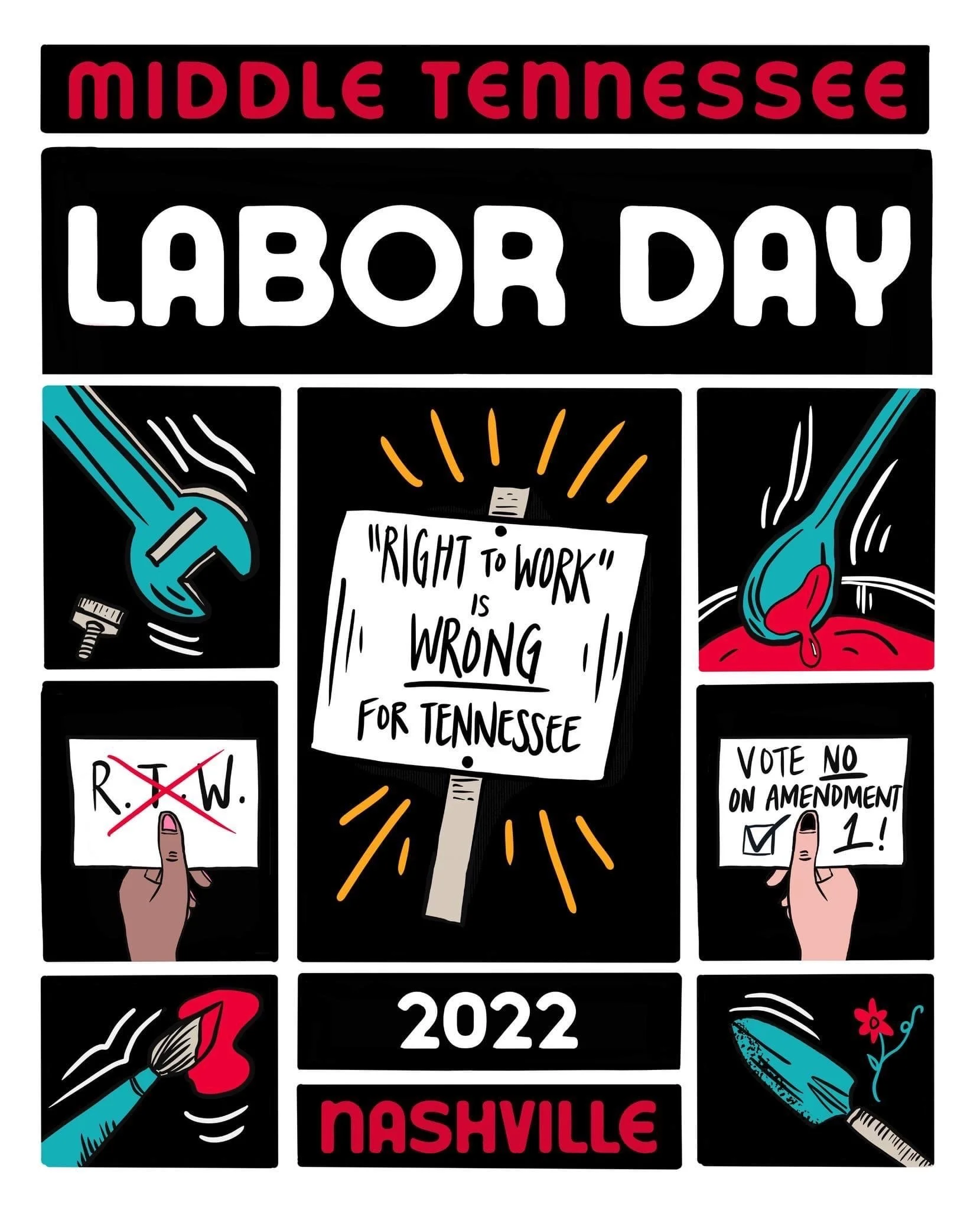

Working people have been on the move in powerful and creative ways over the last 12 months. From employment trends like the “great resignation” to the wave of work stoppages that was dubbed “Striketober,” from the successful grassroots unionization efforts by Amazon workers in Staten Island to Starbucks workers organizing their stores nationwide, working people and their organizations (labor unions, worker centers) have been steadily organizing and helping to raise the labor consciousness of the nation. Here in the South and Tennessee in particular, the labor movement and its allies face tremendous challenges in confronting an incredibly anti-union (and anti-worker) political and economic climate and yet continue to find proactive ways to organize and build people power.

But how often has the actual significance of Labor Day been emphasized in our worshiping communities, and how often have congregations been encouraged to examine the relationship between faith and labor or the plight of working people in our communities and among our pews? As we grapple with the ongoing impact of the pandemic on all who have to work for a living, we cannot let Labor Day pass us by without critically examining our faith in light of our oppressive economic and political systems that trample upon both people and planet. Simply put, there is no time like the present to engage in multi-faith acts of solidarity that bridges faith, labor, and the many structural injustices that have been made ever more apparent in recent years.

It is our hope that these short reflections provide theological and practical tools for honoring the dignity of labor this Labor Day and beyond through tangible actions. Join us in the effort of reclaiming the longstanding tradition of faith-informed solidarity and witness around issues of labor!

Contributors: Joerg Rieger; Francisco Garcia; Vonda McDaniel; Larissa Romero; Yaheli Vargas-Ramos

Want to explore more resources on faith and labor. Check out our collection, here!

Which Side are you ON?

Joerg Rieger

August 10, 2022

“Which side are you on?” This is the chorus of a well-known labor song that originated in Harlan County, in southeastern Kentucky in the 1930s. It was written by Florence Reece, the wife of coal miner and union leader Sam Reece, after she and her children were terrorized by the local sheriff and his men when they entered her house in search of her husband.

Like many working families, the Reeces experienced not only the abuse of law enforcement and military, which often ended deadly for the workers who organized themselves (the US has had the bloodiest labor history of any industrialized nation in the world). Like many workers, they also knew that work itself is often a matter of life and death. Even today, black lung disease is killing coal miners, lack of safety equipment is killing construction workers—and much work in the United States no longer provides living wages for families.

The Israelites to whom Moses speaks in Deuteronomy made similar experiences: They were exploited by an empire designed to secure wealth and power for the few at the expense of the many, and they were systematically terrorized by its slave drivers (Exodus 1:11). Like an ever-growing number of working families today, the Israelites knew that work could be a matter of life and death.

The question, “Which side are you on?” becomes a matter of life and death when exploitation and extraction are the rule and when power and wealth are distributed unevenly between the many and the few. Both in ancient Egypt and in the United States today the rich keep getting richer at precisely the same time when the poor are getting poorer, and the environment is ravaged. Conventional promises that “a rising tide will lift all boats” ring increasingly more hollow.

Working people are often misled into siding with the privileged few rather than the many. White supremacy, for instance, fools white working people into thinking they have more in common with their white bosses than their non-white co-workers. Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly clearer on what side the proverbial 99 percent who work for a living belong.

The biggest surprise, perhaps, is that God also takes sides. The ancient Exodus stories shared by Jews, Christians, and Muslims leave no doubt: God is on the side of the slaves rather than their masters. The book of Deuteronomy, from which our text is taken, continues the theme. There, God demands that orphans, widows, and strangers be treated fairly, and God cares about the poor, reminding the Israelites of their own poverty as enslaved people in Egypt (Deuteronomy 24:19-21).

In times when exploitation, extraction, and inequality are the rule rather than the exception, taking sides is not optional. Unfortunately, the so-called “culture wars” in the United States continue to mislead us, both in politics and in religion. Conservatives seem to be determined to take the side of the privileged few rather than the many, and many liberals tend to respond by refusing to take sides and aspiring to love everyone, even if it kills both people and the planet.

The good news is that there is another option: if the book of Deuteronomy and Florence Reece are right, there are ways of taking sides that are life-giving rather than death-dealing. This insight might bring together people of different faiths and people of no faith who are working together for life and flourishing, against the threat of death and destruction and the false gods of exploitation and extraction.

Joerg Rieger is the Distinguished Professor of Theology, Cal Turner Chancellor’s Chair of Wesleyan Studies at Vanderbilt Divinity School and Graduate Department of Religion, Affiliate Faculty, Turner Family Center for Social Ventures, Owen Graduate School of Management, Vanderbilt University, and the Founder and Director of the Wendland-Cook Program.

Letting the Prophetic Reshape Us

Francisco García Jr.

August 10, 2022

Among the prophets, Jeremiah has often been pegged as the prophet of wrath for the messages of doom and gloom that he brings to the people of Israel. But as Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel has pointed out, Jeremiah more accurately lived “in an age of wrath,” and as a prophet, was obligated to speak to the times. While we don’t have the details about the wrongdoings of the people in these verses, we hear Jeremiah urge the people to “turn now…from your evil ways” (18:11). The imagery of God as the potter, of the clay that spoils in the potter’s hands, and the potter’s ability to rework the clay (18:3-6) — all demonstrate how the people of Israel had strayed from God’s intended path and faced a critical moment of reshaping or destruction.

Earlier in the Jeremiah text, the prophet tells us repeatedly that the people were amassing wealth unjustly, growing rich and powerful by dishonest means, neglecting the orphan, and oppressing the needy (5:25-29; 8:10; 17:11). In God’s eyes, these unjust practices were a central part of the people’s shift to idolatry, of worshiping other gods and denying the true God that liberated them and showed them the way of just and cooperative living. They had become like the spoiled clay, and it was uncertain just how and if they would be remolded. More than wrath for wrath’s sake, the prophetic tradition teaches us about righteous indignation — that perpetuating structural injustice in any form is idolatry, a form of denying the divine among us, of failing to love our neighbor as ourselves.

What might Jeremiah say to us today as we approach Labor Day, a day where we acknowledge the dignity of all who labor? Might he call out the CEOs of the S & P 500 corporations, whose compensation has continued to soar to 324 times the median worker’s pay, while real wages for workers have dropped? Might he single out the corporate leaders of Amazon and Starbucks for spending millions of dollars to silence their workers and prevent them from engaging in their federally-protected right to unionize? Might he fault the rest of us for not doing more to question our extractive economic and political systems that perpetuate wealth and power inequities and ecological degradation, while the vast majority of people struggle for their daily bread? Might Jeremiah implore us with what Dr. King called “the fierce urgency of now” to organize to amend our evil ways as a society and protect both people and the planet?

While Jeremiah did not see much to celebrate in his time, he did point to the possibility of redemption. God’s presence is felt most among the people when they act justly and resist oppression (7:5-7). God as the potter and the people as the clay points less to a predetermined state for the people and more to open-ended possibilities for liberative transformation. The future is not fixed. People can change, systems break down, new realities emerge.

We can allow ourselves to be molded by a culture and political-economic system rooted in injustice, division, and strife, or we can choose to reshape oppressive structures into new ways of being and acting together — a life of solidarity. And it is already happening. We can take heart knowing that much of the new organizing that is taking place is occurring at a grassroots level. From schools to hospitals, retail shops, warehouses and coffee shops, people are coming together and claiming their dignity at work and in their communities. As the working world is being reshaped by the resurgence of everyday people organizing for justice, preachers and faith communities can play a crucial role in reflecting on their own context, listening to the working people in their pews, and getting on board with God’s open future for justice.

Rev. Francisco Garcia, Jr. is the Graduate Research Fellow and Student Leadership Representative at the Wendland-Cook Program in Religion and Justice, and is a PhD Student in Theology at Vanderbilt University in the Graduate Program of Religion.

Bold, Brave and Prophetic Confession for Labor Justice

Vonda McDaniel

August 10, 2022

On Labor Day we honor the contributions that workers have made in our communities, state and country. Unlike other holidays, generally we do not reflect on how Labor Day should be viewed within the religious traditions that influence our daily living. How does our faith show up in our commitment to ensuring the dignity of all work? Charles Spurgeon writes about Psalm 138 by saying “we see the excellence of brave confession. There is a time to speak openly lest we be found guilty of cowardly non-confession.” Like other Psalms in the section attributed to David, Psalm 138 praises God. However, it also acknowledges the presence of trouble—-of enemies. Even in the previous Psalm there is reference to singing in a strange land when we are banished from our own temple and country.

This year we are definitely in a season of brave confession and have witnessed displays by workers discontented with the politically hostile climate they have suffered under for so long. Take for example the fact that the federal minimum wage, the benchmark for hourly earnings, has been stuck at $7.25 since 2009. In many states throughout the country bold advocates and their policy makers are raising wages. In January an Executive Order raised the minimum wage to $15 per hour for federal workers and contractors. Other states and large companies have followed suit.

Workers are celebrating union wins across the country from the Amazon warehouse in Staten Island, New York to Starbuck stores across the country. In fact there are several sources that say that support for unions is at one of the highest levels in history. Even with all the enthusiasm for unions, it is important to acknowledge that only 10.3% of workers are Union members. Forty-eight percent of non-union workers stated they would join a Union if they could and 69% of young workers who say labor unions have a positive impact on the country.

The feeling of thanksgiving and praise that we feel on Labor Day should not obscure the challenges that workers are experiencing. Without confessing that poverty continues to plague our communities and nation, the recent positive jobs numbers, a 3.5 % unemployment rate and other measures of the economy could mislead our analysis. In fact the most recent ALICE (Asset, Limited, Income, Constrained, Employed) report tells another story of how community members work every day but still struggle to survive. Across TN, 47 percent of households struggle to afford the basic necessities of housing, child care, food, health care and transportation. When COVID hit, more than 800,000 Tennessee households were one emergency away from financial ruin. These facts challenge the narrative that all is well and that we should just celebrate the accomplishments of the past year because that is what we do on Labor Day.

We have to continue to grapple with the fact that our economy creates more low-wage jobs than family-sustaining ones. Labor Day must challenge us to confront these uncomfortable truths and commit as people of faith to look at the realities of how right to work laws, tax breaks for the wealthy, structural racism, sexism and all the other isms force many of our brethren to live outside the promised inheritance we all believe is possible. Only by using a bold, brave prophetic voice can we make the kind of change that is needed in the world today.

Vonda McDaniel is the president of the Central Labor Council of Nashville and Middle TN, AFL-CIO and a lifelong member of the First Baptist Church, Capitol Hill.

The Divine Urgency of Relational Justice

REv. Larissa Romero

August 10, 2022

As the numbers of followers increase during Christ’s ministry, he turns to share words: “Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple. Whoever does not carry the cross and follow me cannot be my disciple.” (Lk 14:26-27) I find the word “hate” coming from the voice of incarnate divinity particularly uncomfortable. In my earlier days of ministry, when the organizing militancy I still respect was more internally charged, I would have said Christ was willing to sacrifice community members, including myself, for the vision of the community. If you are “truly” to be a student of Christ, if you are actually picking up the cross, then you have to be prepared to sacrifice for the kin-dom vision - even if it includes your long-held, dearest relationships. I held staunchly onto this interpretation to the edge of burnout.

Then one day I read a quote of Bonhoeffer, wherein he suggests that we can in fact make idols of the very communities we seek to love and build, writing, “Those who love their dream of a Christian community more than they love the Christian community itself become destroyers of that Christian community even though their personal intentions may be ever so honest, earnest and sacrificial…Those who dream of this idolized community demand that it be fulfilled by God, by others and by themselves…” In my own early years of ministry, I could see that I was creating this idol. I also began to recognize that, without dismissing the urgency for church folk to address our interconnected needs for liberation, there was an inescapable complexity to the folks I ministered alongside; it revealed another urgency - the urgency to grow momentum and energy for the work rather than foster disconnection through calling out, guilting, or performative martyrdom. There is an urgency to dismantle the idolization of the “true” community (even if it’s our idea of family or living our best lives), which too willingly cuts off the very relationships that ground the enterprise of kin-dom building.

Organizer Adrienne Maree Brown in Emergent Strategy puts the urgent need for transformation of relationship in the context of fractals: “Patterns emerge at the local, regional, state, national, and global level - basically wherever two or more social change agents are gathered…and this may be the most important element to understand - that what we practice at the small scale sets the patterns for the whole system…Grace [Lee Boggs] articulated it in what might be the most-used quote of my life: ‘Transform yourself to transform the world.’”

According to Strong’s, the Greek “miseo” translated as “hate” in Luke 14:26 has a particular connotation: “identifying preference of one thing by displaying aversion for the other.” Perhaps when Christ asks us to prefer learning to love God to our own kin and very lives, it is to instill in us the immediate, urgent need to transform our personal relationships prioritizing the love of God. Only with the love of God as our foundation can we proceed to live in right-relationship with one another, which necessarily fractals out to a just world. Perhaps Christ offers us an invitation to reset our relational patterns, which need not be those patterns into which we were born or enculturated. Perhaps we can seek being made new to resonate all more with our neighbors’ inherent dignity, good work, and beauty.

Larissa Romero is Pastor at Downtown Presbyterian Church in Nashville. She comes from serving Pascack Reformed Church in Park Ridge, New Jersey as solo pastor. Prior to that call, she worked at Scarsdale Congregational Church in Scarsdale, New York and Greenpoint Reformed Church in Brooklyn.

El costo del No-discipulado: La dignidad humana

Yaheli Vargas-Ramos

August 10, 2022

¿Qué significa tomar nuestra cruz y seguir a Jesús de Nazareth en el contexto de la celebración del Día del Trabajo? Jesús no sufría de narcisismo. Su misión no consistía en su propia exaltación, sino proclamar el reino de justicia, un reino contestatario, en donde los últimos serían primeros y en donde los excluidos serían exaltados. La “jesuuatría” es peligrosa; por querer exaltar su persona, podemos olvidar la justicia por la que él tanto luchó. La exigencia que encontramos en el Evangelio de Lucas 14:25-33, en donde Jesús pide que renunciemos a todo y le sigamos en discipulado, se puede entender como un llamado a matricularnos a su misión de liberación. Tomar la cruz como dijo el sacerdote y poeta nicaragüense Ernesto Cardenal, era reconocerse como subversivos frente al poder imperial que explotaba al campesinado en Palestina.

En este pasaje podemos observar que las multitudes seguían a Jesús de Nazareth. Sin embargo, Jesús no estaba interesado en simples “seguidores”, sus palabras y acciones no eran guiadas por un populismo simplista, dicho de otro modo, buscar “likes” no era parte de su ministerio. El llamado de Jesús era una invitación hacia el discipulado. Este discipulado lo requiere todo, incluso el rechazo de tradiciones familiares que no nos permiten avanzar en la lucha por la justicia.

Renunciar a nosotros mismos, es también renunciar al individualismo, al egoísmo. En el escenario laboral esto significa entrar en solidaridad con nuestros colegas trabajadores, para luchar en contra de la explotación laboral al cual somos sometidos. Esto no es tarea fácil, pues requerirá que rompamos con nuestras rutinas, prejuicios, entre muchas otras cosas más, y comencemos a construir poder colectivo que nos permita hacer frente a las imposiciones laborales que sufrimos hoy.

Las dos pequeñas parábolas que Jesús utiliza en este pasaje (la construcción de una torre y el cálculo de ir a la guerra, v. 28-32) muestran que seguirlo tiene un costo. En el escenario laboral, este costo de seguir a Jesús se puede materializar desde hechos tan simples como en el recibimiento de epítetos (comunista, radical); que nos suspendan del trabajo como le sucedió a Chris Smalls como represalia a su trabajo organizativo, o incluso hasta la misma muerte como les ocurrió a los mártires latinoamericanos Chico Mendes y Berta Cáceres Flores.

Sin embargo, también tenemos que entender que no seguir a Jesús, o lo que es lo mismo, no luchar por la justicia por la que él tanto luchó, también tiene un precio. El costo del no-discipulado puede ser incluso hasta más alto, pues lo pagamos con condiciones laborales deplorables, con la pérdida de poder y agencia propia, en fin, con la plusvalía que termina en manos de unos pocos. En última instancia es nuestra dignidad colectiva la que está en juego. Bien lo dijo el líder sindicalista César Chávez: “No hay nada más vergonzoso y tal vez más deshonroso que la persona que se ofrece a trabajar por salarios bajos... Valorarse a sí mismo como algo barato es un crimen contra la decencia humana... Todo individuo está dotado de dignidad.” Ciertamente Jesús creía en la dignidad intrínseca de todo ser humano, por eso vivió como lo hizo, y aquellos que hemos aceptado el costo de seguirlo, debemos vivir en esa misma solidaridad.

Yaheli Vargas-Ramos is a student at Vanderbilt Divinity School and a fellow at the Wendland-Cook program

Faith and Labor Resources:

Check out the resources below in addition to the above reflections on the lectionary Scripture readings for Labor Day 2021 written by Wendland-Cook staff and colleagues. Included below are a collection of existing faith and labor resources and links to outside resources from partners.